A Process Christmas

by Carolyn Roncolato

The standard Christmas story- preached from pulpits, performed in pageants, colored on cards, and sung in songs- depicts Jesus as some sort of perfect God baby- “the cattle are lowing, the baby awakes, but little lord Jesus no crying he makes.” Christian loyalty to Greek philosophy has lead to an over concern with Jesus’ physical makeup. The answer to the question of how Jesus can be both God and human is often to present him as the most perfect human; one who doesn’t actually behave like a human at all.

As a number of process theologians have argued, Whitehead’s non-substance based, relational metaphysic offers a new way out of the “is he human or divine” problem and a new way into the depth of the nativity narrative. Whitehead suggests that we are not made up of units of concrete elements that determine which thing we are- i.e. God stuff or human stuff or rock stuff or animal stuff etc… Rather, we are fundamentally made up of relationships- with other beings in the world, with our past selves, with ancestors, with God.

As part of our relational becoming, we incarnate God by hearing and acting on God’s call in the world. Looking at reality in this way changes the meaning of the incarnation in a few key ways…

- It is possible to be human and to incarnate God. In other words, humanity and divinity are not mutually exclusive substances or identities. More importantly following God or becoming Christ-like does not require the abandonment, dismissal, or punishment of bodies- either our own or others.

- Jesus was not the only incarnation. The nativity story is not the story of a single miraculous event but rather the revelation that people can express God in the world. Jesus’ incarnation was indeed special, which is a longer conversation, but it was also a testament to the capacity of humanity to do God’s liberatory work in the world.

- Incarnation is not a one-time act. It’s an ongoing process in which God’s call is heard over and over again and acted on continuously. Jesus was not only born the Son of God but became it. The incarnation happened over the course of his life.

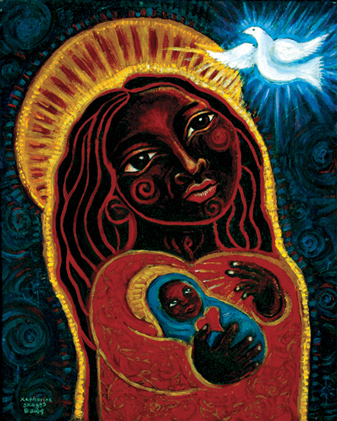

- Lastly, Jesus’ relationships made him who he was. Not only his relationship with God but with his family, his ancestors, his context, and his community. In particular, Mary was not an empty vessel, chosen at random. Who she was, where she was, and how she was in the world all made a difference to the person Jesus became.

So yes, then nativity matters. Not because it’s the miraculous story of a virgin birth of a God baby but because it is a revelation of the sacredness of all human bodies, a testament to big hope born in small and mundane ways, and a reminder that it’s a life’s work to incarnate the call of God.

“In everything which gives us the pure authentic feeling of beauty there really is the presence of God. There is as it were an incarnation of God in the world and it is indicated by beauty. The beautiful is the experimental proof that the incarnation is possible.” (Simone Weil) Thank you for your short, clear interpretation of incarnation in process theology. I know that, historically, Jesus was probably not a perfect God baby. All that you say is, to my mind, on point. I do wonder, however, if the image of the nativity scene, including the baby fast asleep in a manger, doesn’t function as a lure toward beauty for many in a quiet, trans-affiliated way. Whitehead was not much interested in the historical Jesus in any kind of doctrinal detail, except insofar as Jesus invites an alternative view of God. He calls it the Galiliean vision. But in Adventures of Ideas he speaks of the image of mother and child as offering a kind of peace for which all hearts yearn. An avant-garde musical group from England , influenced by Orthodoxy, called The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus, creates musical icons for our time (so they hope) which build upon these archetypal themes of nativity and healing of the heart. (they don’t hide from the hard stuff either: pain, death, abandonment; they know that beauty is not prettiness.) But what draws this musical group is the same things that draws Whitehead: the beauty of the story as an archetype for the imagination. Perhaps a process approach to Christmas can have two sides: one archetypal and one historical. Here’s an archetypal version indebted to Whitehead, Simone Weil, and the Revolutionary Army: http://www.jesusjazzbuddhism.org/tenderness-and-beauty-the-revolutionary-army-of-the-infant-jesus.html.